There is no question that even the most treasured of our friends and relatives make poor company after death. All human societies in existence, from the most primitive to the most technologically sophisticated, have specific funereal customs for dealing with that inevitable but awkward transition from the living person to the decaying corpse. Throughout human history, the proper disposal of the dead has been regarded as a matter of great moral as well as emotional importance. In fact, the earliest human remains that show signs of deliberate burial are generally accepted as evidence that these ancient Homo sapiens had attained some level of spirituality. Skeletons of Neanderthals who died some 50,000 years ago have been found entombed, usually sitting upright or curled in the fetal position, with tools and other possessions arranged around them. Contemporary burial traditions are diverse, but all combine the hygienic necessity of removing a corpse from the company of the living with a set of rituals that assist the survivors in rationally and emotionally accepting their loss.

There is no question that even the most treasured of our friends and relatives make poor company after death. All human societies in existence, from the most primitive to the most technologically sophisticated, have specific funereal customs for dealing with that inevitable but awkward transition from the living person to the decaying corpse. Throughout human history, the proper disposal of the dead has been regarded as a matter of great moral as well as emotional importance. In fact, the earliest human remains that show signs of deliberate burial are generally accepted as evidence that these ancient Homo sapiens had attained some level of spirituality. Skeletons of Neanderthals who died some 50,000 years ago have been found entombed, usually sitting upright or curled in the fetal position, with tools and other possessions arranged around them. Contemporary burial traditions are diverse, but all combine the hygienic necessity of removing a corpse from the company of the living with a set of rituals that assist the survivors in rationally and emotionally accepting their loss.Jewish, Christian, and Muslim traditions mandate burial of the dead after ceremonial cleansing and shrouding of the body. All arrange the corpse in an extended position, but while Jews and Christians place the deceased in the familiar "toes up," supine orientation, Muslims bury the body lying on its right side, facing in the direction of Mecca. Hindus traditionally cremate the body, as did the more prosperous of the ancient Greeks and Romans. The corpse's former possessions and other offerings may be added to the funeral pyre; in former times, a Hindu wife was occasionally prevailed upon to join her deceased husband in his return to simpler carbon. Another approach to the disposal problem is used by the Parsees, a branch of the Zoroastrian sect who fled to India from their native Persia. These people traditionally have placed their dead upon raised platforms, eerily but appropriately named Towers of Silence, to be devoured by vultures and other scavengers. However, in recent years, the collapse of vulture populations has threatened the feasibility of this method.

Getting rid of the body has not always meant a prompt and complete disposal of the remains. Consumption of the dead, or portions thereof, by the surviving relatives was customary in aboriginal populations of the Americas, Africa, and Australia. A formal gesture of respect that symbolized continuity between the deceased and succeeding generations, this tradition did, however, prove disadvantageous to at least one group of adherents. The Fore tribe of New Guinea had long baffled medical scientists with the high frequency of kuru, a degenerative and usually fatal neurological disease, occurring among its members. A particularly puzzling aspect of the malady was the observation that it affected primarily women and children. Believed to be caused by an infectious agent, similar to the one responsible for bovine spongiform encephalopathy and its human counterpart, Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease, kuru had been attributed to the tribal practice of ingesting brain tissue from dead relatives. Females of the family were responsible for preparation of the dead body, and in some cases the necessary ritual included rubbing the infected brain tissue over the bodies of women and children relatives of the deceased. Fortunately for the Fore tribe, the incidence of kuru has diminished in parallel with the decline in popularity of this funerary tradition.

Grotesque as the custom may seem to us civilized Homo sapiens, feeding upon the dead is the rule rather than the exception through the rest of the natural world. Because the organic and mineral components of animal bodies are in limited supply and hence too valuable to waste, a variety of organisms have adopted a way of life based upon the consumption, and hence decomposition, of dead animal remains. And as with any other rich nutrient source, carrion inspires vigorous competition among the organisms that subsist upon it; even such microscopic beings as mites, fungi, or bacteria may make some effort to monopolize the dead tissue they grow upon. The toxins released by various putrifying bacteria, for example, are thought to be defense mechanisms by which these organisms exclude arthropods and vertebrates from sharing their food supply ("Go on!" gloated the Salmonella bacillus. "I just DARE you to taste this week-old shrimp salad!")

Many predaceous animals do eat carrion when the opportunity arises: badgers, opossums, shrews, and any number of rodents; crows and gulls; and crustaceans such as shrimp, lobsters, and crabs (as that memorable scene depicting the discovery of Jaws's first victim-- greatly reduced in bulk but still a treat for the local crabs-- so eloquently demonstrated. Connoisseurs of shellfish who become overly familiar with the gustatory habits of these animals have to achieve considerable broad-mindedness, or an active state of denial, in order to continue enjoying such delicacies.). Other animals make their entire living, so to speak, by disposing of the dead.

One of the most conspicuous consumers of carrion is the vulture. Large mammal corpses are especially abundant on the teeming plains of Africa, and the African vultures, which have developed specializations for utilizing different parts of the corpse, are commensurately diverse; as many as nine species of vulture may be found feeding at a single carcass. Species like the hooded or Egyptian black vulture (Aegyptus monachus), with their substantial bodies and heavy beaks, have the strength to tear through the hide of large animals, thus opening up the carcass for other scavengers. These species have bare faces or heads, but their necks are fully feathered; they feed primarily at the surface of the carcass. (The characteristic bare skin of vultures is believed to be a hygienic measure that allows rapid drying in the sun, thus reducing the likelihood of bacterial infection from the putrid flesh they gorge themselves with.) Other vultures such as the griffon (Gyp fulvus) have long, bare necks and are adapted for digging deep into the carcass.

The New World of today has less extensive large mammal populations, and hence fewer species of vulture, than does Africa. However, the Andean condor (Vultur gryphus) is the largest vulture, and hence the largest flying bird, in the world. Like their Old World counterparts, these birds are expert gliders, soaring over extended distances to find carrion, which they locate primarily by sight. The black vulture (Coragyps atratus) and turkey vulture (Cathartes aura) range through much of North and South America. The black vulture tends to soar high above ground, like the condors, and searches visually for food, while the turkey vulture, in contrast to most birds, has a highly developed sense of smell and flies quite low while hunting. Unlike so much of our native wildlife, black vultures have embraced human civilization, feeding happily upon garbage in addition to their more traditional menu.

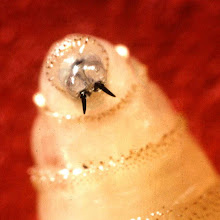

Dramatic and symbolic as the vultures are, however, they claim a relatively low proportion of animal matter available for disposal; insects are by far the most important of the visible decomposers. Among the most familiar, and frankly, repulsive consumers of corpses are the flies. Blow flies (family Calliphoridae) and flesh flies (family Sarcophagidae) lay their eggs upon dead animals, and their larvae burrow through and consume the rotting flesh. Adult flies in search of a nursery establishment are capable of detecting and locating corpses within minutes of death, and competition for carrion is intense. As a result, larval flies, or maggots, tend to eat, digest, and grow rapidly; the metabolic heat released by their combined numbers can be remarkable. One worker reputedly placed 10 grams (1/3 ounce) of washed maggots in a thermos bottle and measured their temperature; within 30 minutes the seething mass of maggots had raised the temperature in the flask from 65 degrees F to 100 degrees F.

Among the other insects that covet rotting flesh as a resource for their young are the carrion beetles (family Silphidae). Some of these beetles-- several species of Necrophorus, for example-- take extreme measures in order to acquire exclusive use of a corpse. These so-called "sexton beetles" can bury small animal carcasses several inches underground within a day or two. Several individuals may begin the process, but once the job is done, the beetles fall to fighting viciously among themselves. Males against males and females against females, they battle to the death, until a single eligible couple remains. This happy pair proceeds to mate and deposit eggs in the corpse, and their larvae feed and grow in their underground larder; in some species, the parents even sustain their young offspring personally by regurgitating partially digested carrion into their larvae's mouths.

But moving on from this tender family scene, the skin beetles (family Dermestidae) consume the more persistent components of carrion, including skin, hair, and other connective tissue, as well as any lingering flesh. However laudable this ability may be from the standpoint of nutrient recycling, it may represent a serious nuisance to Homo sapiens when the beetles find their way into human habitations and storage facilities. Dermestid beetles can feed upon carpets, fur garments, and leather furnishings or book bindings, in addition to more obviously edible items, including many kinds of bulk foods. These animals are particularly problematic in museums, where they may reduce insect collections and vertebrate skin specimens quite literally to dust. One species (Dermestes caninus) has, however, been put to practical use in the otherwise tedious process of cleaning bones to be used for the construction of mounted skeletons, and has therefore partially atoned for the destructive acts of its relatives (note to movie buffs: this species has a fleeting but memorable cameo appearance in the 1983 movie “Gorky Park”).

Despite the gruesome stereotype perpetuated by the beetles, flies, and vultures, not all decomposers present an unattractive aspect. The Central American butterflies Caligo memnon, Hamadryas februa, and Historis odius, all indisputably lovely, feed upon plants during their larval phase but sustain themselves as winged adults by nibbling daintily upon carrion. Chipmunks (Tamias striatus) and other cute little ground squirrels who live along roadways are not above taking a few bites out of former colleagues who have perished under the wheels of automobile traffic. Even the songbirds that flock to our winter feeders to feast upon suet are reflecting an age-old enthusiasm for picking the richer tidbits from exposed carcasses. Lest we shrink in disgust from these fellow-creatures, let us consider that their ghoulish habits help return precious nutrients to circulation, and tidy up the environment to boot. And after all, the distance from last year's dead sea gull to this year's shrimp scampi may be shorter than we think....

Copyright 1993. All rights reserved.